1. The

novelty of the issue

This

article deals with the vexatious question of how to conceptualise the

human person as a living subject (i.e. having an existence, meaning ex-sistere:

to be out), from the viewpoint of the social sciences broadly understood,

by commenting upon Margaret Archer’s recent book on the “internal

conversation” (Archer, 2003). The main difficulty does not consist in seeing what

a human person is made of (i.e. the unity of body and mind, the continuity

of a “substance” together with its “accidents”, etc.), but what relates

the single components of the human person (their properties and powers) to

themselves and to the external world.

Archer

deliberately starts the story from the Enlightenment. Why does she do so?

Why not to start from previous eras, as scholars often do, particularly

when trying to define the human person? The answer is trivial, but it

deserves to be explained: the answer is that the social sciences she is

talking about have been born with modernity. The attempt to tackle the

issue by going back to previous conceptualisations would be vain. This is

so for two main reasons.

i) The

issue, as Archer proposes it has not been “thematised” (understood as a

theme in itself) before the modern epoch. In other words, “the social

dimensions” of the human person in his/her inner and outer life do not

represent a meaningful and central issue per se in pre-modern

thought, from ancient Greece to the Middle Age. So much so that, if we try

to understand the social dimensions of the human person by relying upon

the classical philosophical categories, we come across “natural

explanations” which cannot grasp the reality we are trying to explain.

ii) The

challenges issued by modern and post-modern society to the very existence

of the human person have no precedent in the history. These challenges are

so great and radical that they require the elaboration of a new paradigm,

based on a social ontology able to comprehend the empirical evidences as

offered by the social sciences. For the first time in history, our society

describes itself as non-human, and even anti-human, in deeply conscious

and convincing ways.

To put

it bluntly, the issue of understanding the human person from the viewpoint

of the social sciences can certainly resort to the wisdom and knowledge of

the classical thought, but cannot find a solution within it. The basic

reason for that is that modernity has generated the issue of the social

relationality inherent in the human person on the basis of modalities,

which did not exist before the explosion of modernity. The unity of the

human person has been submitted to processes of differentiation in every

dimension. The relations between the differentiated dimensions (what one

calls today “the process of individualisation of the individual”) cannot

be approached by applying to pre-modern knowledge categories.

In

which way and to what extent this situation implies a revision of

classical metaphysics is a topic that has been largely perceived, but

certainly not solved. The revision should take into account the fact that

classical metaphysics deals with the human person within the general

ontology of entia, while the modern turn implies a distinct

ontology of the human person as different from the other entia

(Polo, 1991, 1993). The issue put forward by Archer appeals to an ontology

of “the social” which is still to be fully developed.

Classical philosophy has conceived of the social as a pure “accident”,

which can be separated from the substance or nature of the ens (Fabro,

2004). If we conceptualise the “sociability” of the human person as “relationality”

which is “constitutive” of him/her, we must go further than the

distinction between substance and accident. We must treat the relational

character (natural, practical, social and spiritual) of the human person

as co-essential to his/her existence and to our understanding.

Archer

responds to the challenge. She does so in an original way, in a

distinctive way in respect to almost all those thinkers who have dealt

with the same issue, for instance M. Buber and M. Heidegger and, as

concerns sociology, the various schools which go back to the classics

(Durkheim, Weber, Pareto and Simmel). They are rightly put under the

headings of reductionist and conflationary theories.

2.

Archer’s thesis about the shortcoming of modernity in dealing with the

human person and the need for a new perspective

Archer

maintains that modernity has brought about an issue, the relational

constitution of the human person, while treating it on the basis of

distorted approaches, which cannot account for what really generates and

regenerates the human person. In her opinion, the sociological problem of

conceptualising the person is how to capture someone who is both partly

formed by their sociality, but also has the capacity to transform their

society in some part. The difficulty is that social theorising has

oscillated between these two extremes. On the one hand, Enlightenment

thought promoted an “undersocialised” view of man, one whose human

constitution owed nothing to society and was thus a self-sufficient

“outsider” who simply operated in a social environment. On the other hand,

there is a later but pervasive “oversocialised” view of man, whose every

feature, beyond his biology, is shaped and moulded by his social context.

He thus becomes such a dependent “insider” that he has no capacity to

transform his social environment.

Archer

points out that modernity is intrinsically unbalanced: it sees only the

over-socialisation and the under-socialisation of the human person. The

well-known distinction between homo sociologicus and homo

oeconomicus is based on these reductions.

Archer

claims that the dilemma lies in the circular loop which links the person

to society: the person is “both ‘child’ and ‘parent’ of society”, the

generated and the generator at the same time. We need a new scientific

paradigm to understand how the human person can be both (a) dependent on

society (a supine social product) and (b) autonomous and possessing its

own powers (a self-sufficient maker). Classical philosophical thought has

coped with this dilemma in a quite simple way: it has reduced the

dependence on society to contingency and it has treated autonomy by means

of the concept of substance. A “solution” which refers to a low-complex

and “non-relational” society.

The

idea of classical philosophy, according to which the person is a substance

and society is an accidental reality, cannot be sustained any longer if we

want to understand the vicissitudes and the destiny of the post-modern

man. After modernity, it is not possible to understand social relations

basically as a projection of the human person.

Differently from classical thought, which denies the paradox inherent in

the sociality of man, modernity accepts it and, more than that, it

generates it. But the question is: how does modernity solve the paradox,

granting that it tries to solve it?

Archer

claims that modernity looks for possible solutions by adopting

conflationary epistemologies. And by this way modern social sciences lose

the human person as such. She is undoubtedly right. So we are left

with the task of “rescuing” the singularity of each human person, his/her

dignity and irreducibility, and, at the same time, of seeing the

embodiment and embeddedness of the person in social reality without

confusing or separating the two faces (singularity and sociality). How can

this task be accomplished?

Archer

proposes a better conception of man, from the perspective of social

realism, which grants humankind (i) temporal priority, (ii) relative

autonomy, and (iii) causal efficacy, in relation to the social beings that

they become and the powers of transformative reflection and action which

they bring to their social context, powers that are independent of social

mediation.

These

three operations (i, ii, iii) – as seen from the viewpoint of the social

realism - are not easy to be understood where one wishes to avoid a

desocialised vision of the human person. As a matter of fact, Archer’s

proposal is to open a new perspective (a relational perspective) on the

processes of human socialisation. The novelty lies in prompting that there

is a temporal priority of the person vis-à-vis society (which is

counter-intuitive), in conceiving of autonomy as experience guided by an

internal conversation and by understanding the concept of ‘relative’ as

‘relational’, and by restoring the notion of causality.

These

operations become likely within a theory that, going well beyond modern

social sciences, states that:

-

reality is stratified: whichever kind of reality we are observing, it

is made up with multiple layers, each one possessing its own powers and

emergent properties;

- in

between the layers, there exists a temporal relationality,

which means that powers and properties are emergent effects;

- all

in all, the relationality of the human person is conceivable as a

morphostatic/morphogenetic process.

By

adopting this social theory, based upon a realist epistemology (which is

called critical, analytical, and relational, without being relationist),

it becomes possible to perform some operations which otherwise would be

impossible.

1) We

can see the pre-social and meta-social reality of the human

person, so that the human person cannot be reduced neither to a social

product (conflated with society) nor to an idealistic concept;

2) We

can observe the identity of the self, its continuity and its ability to

mature within and through social interactions, while displaying between

nature and the ultimate concerns.

3) We

can see how the singularity of the human person is realised in a unique

and necessary combination of four orders of reality (natural, practical,

social, spiritual or supernatural), so that the contingency turns into a

necessity if the person must personalise his/herself and thus becoming

‘more’ human.

The

challenge of the widespread argument about “the individualisation of the

individual” is turned into the argument of “the personalisation of the

person”.

3. Why

an after-modern paradigm?

The

sweeping criticism of the modern social sciences worked out by Archer

(what she calls the two complementary faces of Modernity’s Man and

Society’s being) is intended to overcome the modernism itself as a

mentality and as an obsolete scientific paradigm. That’s why I believe

that Archer is developing an after-modern way of theorising about

social reality, and consequently about the human person.

She is

able to show, in a clear and well argued way, how the two main strands of

modern social sciences are now conflating in a particular version (the

central conflation between agency and structure) - which can be also

called the lib/lab conflation - where the human person and the

surrounding society are mutually interacting and generating each other

without the chance to distinguish between different contributions,

properties, powers and the temporal phases of the processes.

As I

have already said, Archer rejects all forms of conflationary thought by

elaborating the paradigm of morphogenesis/morphostasis, based upon a

social ontology in which the human person recovers his/her priority both

logical and temporal, but without getting into a metaphysical abstraction

or an idealist entity. I’d like to reformulate her view in the following

way. I suggest to criss-cross Archer’s scheme concerning the development

of the self (Archer, 2003) (1) with the AGIL scheme as revised in the relational

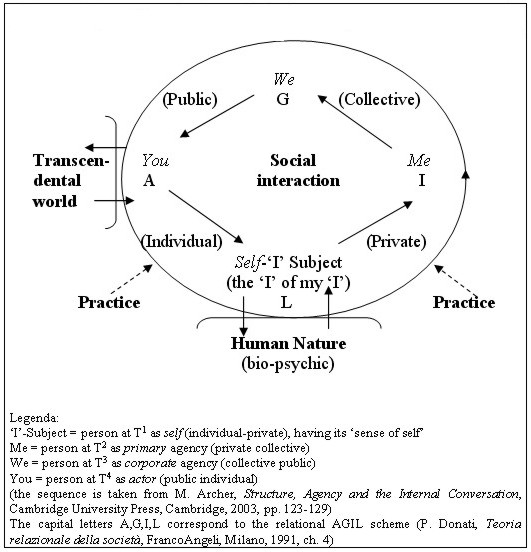

theory of society (Donati, 1991, 2006). (fig. 1).

The

human person is someone who, standing in between the natural world

(bio-physical) and transcendence, develops through social interaction. At

the start, the person is a subject or potential self (“I”) who, through

experience (practice), gets out of nature and becomes a primary agent

(“me”), then a corporate agent (“we”), then an actor (auctor)

(“you”). To me, it is at this point that the dialectic I/you meets the

need to cope with the transcendental world. Then the subject returns on to

the “I” as self. The “exit” from nature must always pass through the

nature again and again. The transcendental reality is treated in the

reflexive phase that the subject realises after having passed through

practice and sociality. Through these passages, the subject becomes a more

mature self-living in society.

Every

mode of being a self (as I, me, we, you) is a dialogue (an internal

conversation) with her own “I”. The battlefields are everywhere. But I’d

like to emphasise that they are particularly meaningful (i) at the borders

between the “I” and the bio-physical nature, (ii) in social interactions,

(iii) at the borders with the transcendental world (see fig. 1). Archer

discusses the third area in detail because this battlefield is the most

underestimated within the social sciences. She makes clear how the human

person can get a progressive divinisation (Theosis) while being in

the world. Figure 1 makes it explicit that the You can go out of the

social and come back to it without living the circle of practice and

experience of the world. That is why the personal identity (PI) emerges as

distinct from the social identity (SI) exactly because the former is in

constant interaction with the latter: but the latter (SI) is subordinated

(i.e. is a sub-set) to the former (PI).

Social

identity is the capacity to express what we care about in social roles

that are appropriate for doing this. Social identity comes from

adopting a role and personifying it in a singular manner, rather than

simply animating it. But here we meet a dilemma. It seems as though we

have to call upon personal identity to account for who does the

active personification. Yet, it also appears that we cannot make such an

appeal, for on this account it looks as though personal identity

cannot be attained before social identity is achieved. How

otherwise can people evaluate their social concerns against other kinds of

concerns when ordering their ultimate concerns? Conversely, it also seems

as if the achievement of social identity is dependent upon someone

having sufficient personal identity to personify any role in their

unique manner. This is the dilemma. The only way out of it is to accept

the existence of a dialectical relationship between personal and

social identities. Yet if this is to be more than fudging, then it is

necessary to venture three “moments” of the interplay (PI<-->SI) which

culminate in a synthesis such that both personal and social identities

are emergent and distinct, although they contributed to one another's

emergence and distinctiveness. By allowing that we need a person to do

the active personifying, it finally has to be conceded that our personal

identities are not reducible to being gifts of society. Unless

personal identity is indeed allowed on these terms, then there is no way

in which strict social identity can be achieved. In the process, our

social identity also becomes defined, but necessarily as a sub-set of

personal identity.

Society

is surely a contingent reality, but contingency does not mean pure

accident. It is in fact the notion of contingency which is in need for new

semantics. Contingency can mean “dependency on” (T. Parsons), or “the

chance not to be, and therefore to be potentially always otherwise” (N.

Luhmann), but it can also mean “the need for personal identity to mature

through social identity”. The third position implies that contingency can

be monitored by the ‘sense of self’, and guided through the internal

conversation of the subject.

Without

this different semantics of contingency, the human person could not take

the steps, which are necessary to go from nature to the supernatural

world, discovering its transcendence in respect to society. This is the

deepest sense of reflexivity as the proper operation of that “internal

conversation” which makes the human person more human. The social

relationality is precisely the fuel or food for the reflexivity, which

makes the human person effective.

Fig. 1 - The conceptualisation of the

human person as someone who develops in between nature, practice, social

interaction and transcendence

If we

apply the AGIL scheme (in the revised, relational version I have offered

in the book “Teoria relazionale della società”: Donati, 1991) to

the sequence I-me-we-you, we can see a quite curious thing: the natural

world occupies the dimension (function) of latency, while the

transcendental world occupies the dimension (function) of adaptation. Why

so? My interpretation is that the self is a latent reality rooted in its

nature, while the means which realise the human person as such do not

consist of material instruments, nor of practices as such, not to mention

the processes of socialisation due to the contrainte sociale, but

consist of its ultimate concerns. From this perspective we can

better understand the meaning of Archer’s statement according to which

“who we are is what we care about“: it means that our self becomes

what it generates in the “I” by way of adaptation to (confrontation with)

the ultimate concerns during the life span.

This

internal work (reflexivity) must be accomplished in the dialogue that the

“I” has with itself, i.e. when the “I” asks who is really its own “I” when

confronted with a Me, a We (fellowship) and a You (one who play a social

role in which ultimate concerns are involved). To operate the distinction,

“the ‘I’ of my ‘I’” does not mean to be self-referential by re-entering

the same distinction (as Luhman thinks): it is also, and at the same time,

to choose which environment to refer to (and therefore it is also an etero-referential

operation, but accomplished by the same identical person). When discussing

with his/herself and deciding where to bring the “I”, one self has to be

both self-referent and etero-referent (this is where “the social” comes

into play).

In

order to understand the process of humanisation of the person, it is

necessary to disprove the epistemic fallacy according to which “what

reality is taken to be, courtesy of our instrumental rationality or social

discourse, is substituted for reality itself” (Archer). In other words, in

order to arrive at a scientific model able to avoid any conflation in the

understanding of the human person as a relational being, it is necessary

to refute what is known today as epistemological “constructionism”, be it

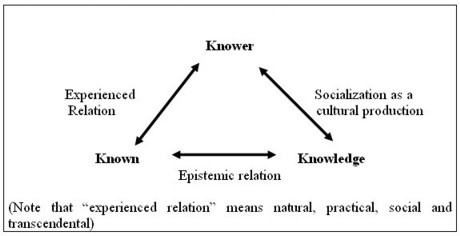

radical or moderate. This can be done by using what I’d like to call the

epistemic triangle suggested by critical realism (fig. 2)

Fig. 2 - The epistemic triangle of

critical realism

As a

matter of fact, most contemporary social sciences claim that: i) the human

person can be known only as a product of knowledge (the person is viewed

as a cultural production of socialisation), meaning that the knower can

only know through the cultural products of the context he lives in; ii)

the relation between knowledge and known is supposed to be relativistic;

iii) the experienced relation of the knower towards the known is reified

(Pierre Bourdieu gives us an excellent example).

Archer

is able not only to criticise all these assumptions, but also to clearly

show how, behind the methodological and epistemological debate, lies an

“ontological issue”. What we are used to call methodological individualism

and methodological holism harbour opposite ontologies that she calls

anthropocentricism and sociocentricism. Only the epistemic triangle can

overcome this fallacies, in so far as it allows us (i) to distinguish

between knower, known and knowledge as stratified realities of different

orders, (ii) to consider their relations as reflexivity driven (instead of

being reified) (fig. 2).

In

Archer’s conceptual framework, personal knowledge is the product of a

complex series of operations, done by the self, through a reflexive

activity in relation to the reality to be known, in which the knowledge

already existing in society (its ‘culture’) is only a given (in systemic

terms: an environment).

Only

this epistemic triangle can valorise the human person as subject and

object of his/her own activity.

4. A

few questions

The

work by Archer offers many suggestions, which should be treated more

properly and more deeply than I can do here. Let me just raise some

questions.

With

reference to my figure 1, we can envisage the following open issues. They

lie a) at the borders between nature and the person in society, b) in the

relationships between the internal reflexivity of the person and its

social networks, c) at the boundaries between the human person and

transcendence.

a) The

border between nature and the person in society (the battlefield of

practical experience) becomes more and more problematic in so far as

society changes nature continuously. Certainly nature reacts. But changes

produced by science and technology are challenging the ability of the

human person to dialogue with nature in its very roots. The question is:

is/will the subject be able to relate itself to nature when society has

made/shall make nature more and more unrecognizable, or fuzzier and

fuzzier? It is evident that changes in the natural world can shift the

thresholds within which the experience of the ‘sense of self’ can be

adequately managed.

b) The

second question concerns the relation between the internal reflexivity of

the person and the social networks he/she belongs to.

The core claim of Archer’s argument is that consciousness should be

understood as emergent, where emergence implies the non-reducibility of

analysis; the epistemological impossibility of the reduction of the

emergent state is determined by the constitutive feature of consciousness,

namely, reflexivity. I agree on that. But, possibly, the

emphasis on the internal reflexivity needs to be connected to the

properties and powers of the social networks in which people live, given

that these networks may have their own “reflexivity” (of a different

kind).

c) The

third set of questions concerns the borders between the person and the

transcendental world. The ability of the human person to connect

him/herself to the transcendental world strongly depends on his/her

ability to “symbolize”, i.e. to understand and appropriate the symbolic

world (to know reality through symbols). The question is: how is this

ability produced in the internal conversation? How is it promoted or

endangered by society? Certainly we must distinguish between different

types of symbols: prelinguistic, linguistic and “appresentative” (in the

Luhmannian sense). But it seems to me that much effort should be made in

understanding the importance of symbols - their formation and their use –

to get a person properly involved in the supernatural. My feeling is that

sociology has reduced the symbols to what sociologists call the “media”

(the generalised media of interchange according to Parsons and the

generalised means of communication according to Luhmann). It is evident

that symbols cannot be reduced to ‘means’ when dealing with the

transcendental world. There is the need to better understand the role of

symbols in Archer’s framework.

To

conclude

The

emergentist paradigm worked out by Archer in order to understand the human

person puts the old query of the relation between personal identity and

social identity in new terms. I have used the word after-modern to

catch it.

Within

the social sciences, the relation Personal Identity

ßà

Social Identity is usually observed as an antithesis by. But it is clearly

not an antithesis. It is an interactive elaboration, which develops over

time, provided that the personal identity side operates it. It can induce

humanisation only by being asymmetric.

We can

therefore go well beyond those scholars who, in the last century, have

thought of the relation between Personal Identity and Social Identity as

something necessarily reifying the person (neo-marxists) or conceiving it

in dualistic terms (for instance Buber, but also Habermas and many

others). The human person must deal with all kinds of social relations. We

need not to oppose system relations and lifeworld relations, good and bad

relations “in themselves”, or warm and cold relations as Toennies referred

to, in so far as what is relevant is the reflexivity of the human

person in dealing with them.

Only

this vision can explain why and how the human person can emerge from

social interactions, while he/she precedes and goes beyond society. In

short, the relation between PI and SI is a dialogue between the lifeworld

(intersubjective relations) and social institutions (role relations), but

it must not be conceived as symmetric, because it is acted by the subject

(agent and actor) who does not want simply to animate a role, but also to

personify it in a singular manner.

Archer’s vision has positive implications in the long run: her critical

realism allows us to give room to, to think of and to promote the

capabilities of the human person to forge a more human society,

notwithstanding the fact that modernity has brought us into an anti-human

era. That’s why I have tried to comment on her book, by saying that the

“economy” of the human beings does not lie on their natural, physical or

material means, but on what fuels their ultimate concerns.

Bibliographic references

Archer, M.S. (2003). Structure, agency and the

internal conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donati, P. (1991). Teoria relazionale della società. Milano:

Franco Angeli.

Donati, P. (Ed.) (2006). Sociologia: un’introduzione allo studio

della società. Padova: Cedam.

Fabro,

C. (2004).

Dall’essere all’esistente:

Hegel,

Kierkegaard, Heidegger e

Jaspers.

Genova: Marietti.

Polo, L. (1991). Quién es el hombre: un espiritu en el mundo.

Madrid: Ed. Rialp.

Polo, L. (1993). Presente y futuro del hombre. Madrid: Ed.

Rialp.

Note

(1)

See

Archer, 2003,

pp. 123-129. [volta]

Note on the author

Pierpaolo Donati is

the founder of relational sociology. He is a professor of sociology at

University of Bologna´s College of Political Sciences and also director of

the Social Politics and Sanitary Sociology Study Center of that university.

Author of more than 500 publications, in Italian and other idioms, Donati

was president of the Italian Sociology Association. Contact: donati@spbo.unibo.it

Data

de recebimento: 19/06/2005

Data de aceite: 30/10/2006

-

-

Memorandum 11, out/2006

Belo Horizonte: UFMG; Ribeirão Preto: USP

-

ISSN 1676-1669

-

http://www.fafich.ufmg.br/~memorandum/a11/donati01.htm